Are We There Yet? Part I

A Personal Look at the State of Black & White Digital Photography

by Harold M. Merklinger

I last took a critical look at digital black and white photography in about 2004. The results of that assessment can still be found on this website. But significant progress has been made since then, so it's time to have another look. Several dedicated ink-jet printers now have dedicated black and white modes using at least three shades of gray ink. Digital b&w is certainly better than it was in 2004, but is it as good as conventional silver-based black and white photography?

Readers of The Luminous Landsape may have noted a certain common theme to some of my articles published there. It’s perhaps time to come clean and explain my agenda. I originally intended this article to be a simple one explaining that the Nikon D800 (or D800E) camera finally fulfills the world need for a 35 mm sized digital camera that is as good in all respects as a 35 mm film camera. It didn’t turn out to be that easy – as I will explain.

The closest I came to reveling my grand agenda was in the article “The Canon 50D Milestone” form December 2008. In that article I noted that near the dawn of the digital photography era, I had “predicted” to friends that one would need 9 megapixels to equal 35 mm colour print film, or 35 megapixels to equal the capabilities of 35 mm black and white film. I had never quantified Kodachrome, but simply indicated that it was somewhere in between. The article “D60 First Impressions” noted my surprise that 6 megapixels seemed to equal or exceed typical 35 mm print film and even invade some aspects of medium format photography. With the arrival of a full frame 36 megapixel camera – the Nikon D800 and D800E – I think this is an appropriate time to review the situation. At the risk of asking the question again: are we finally there yet with digital black and white?

Looking back on the progress of digital photography, I would amend my views slightly. The Canon D60 did not quite provide the resolution of the best colour print 35 mm film, but the 8 megapixel Canon 20D certainly did. 6 megapixels did provide some of the smoothness of medium format colour print film images, but not completely. The 10 megapixel Canon 40D provided me with images almost as good as my 645-format cameras. The quality of my 18 megapixel Leica M9 images exceeds that of all my previous colour work - period. I cannot make any similar statement about black and white photography.

This is a Halifax NS streetscape taken in about 1983 using a Leica M5, 35 mm f/2 Summicron and Ilford Pan-F developed in dilute Microdol-X. The exposure was 1/30 sec at f/8.

In order to fully explain why I care at all about this, I need to go back more that 50 years to when I first began to use a 35 mm camera. I was a highschool student and one of my hobbies was photography. Although I could just afford to buy and operate a 35 mm camera with interchangeable lenses, it was several years before I could afford a longer-than-normal focal length lens. And when I was given one, I found I could not rangefinder focus it well enough for it to be truly useful. My work-around was to use slow b&w film (typically Adox KB14) along with careful focusing and processing to make reasonable-quality highly-cropped prints. I had to learn techniques that enabled highly detailed 35mm images to be made. Michael Reichmann would undoubtedly have called me a pixel-peeper: except that there were no pixels at which to peep back then. I believe the term used was “Grain Sniffer” and I have an array of modest power magnifiers and microscopes to prove it! So, yes, I have been preoccupied for a long time with what lenses, films - and sensors – can do!

It should have been easy for me to obtain a D800, make a few tests and prove “We have finally arrived! We now have a digital 35 mm sized camera that’s every bit as good as film.” It didn’t turn out that way!

You may have been surprised at the gap in the resolution capabilities I ascribed to colour and b&w films. The best b&w films are – or were – really quite remarkable. The “game” I played in my later photographic film life (the 1980s and 90s) was to try to produce 16 by 20 inch b&w prints from 35 mm negatives that rivaled prints normally produced using a view camera. The techniques are well described in the 15th edition of The Leica Manual: use Kodak Technical Pan film, Technidol developer, and the best lenses available, and the best technique one could muster. My goal was to produce 16 by 20 inch prints with detail that required a magnifier to see. Although I did occassionally use Kodak Technical Pan film, I more often used Ilford Pan F - which was almost as good and a lot easier to use. In truth, detailed as they might have been, my prints never did have the natural tonal rendition of true large format camera prints, but it was fun to ask people which print was from a large format camera and which from a 35 mm camera and have them pick the 35 mm image! So this was my standard for the b&w digital requirement; it worked out to something like 35-40 megapixels. I explain the colour to b&w megapixel gap in terms of information theory. B&W images lack the information conveyed by colour and must make up for it through definition and texture. I estimate the true equivalent resolution of some of my 5 by 7 inch b&w negatives is closer to 210 megapixels or thereabouts. And, unlike traditional colour print materials, b&w printing papers can usually support all or nearly all of the detail in the negative.

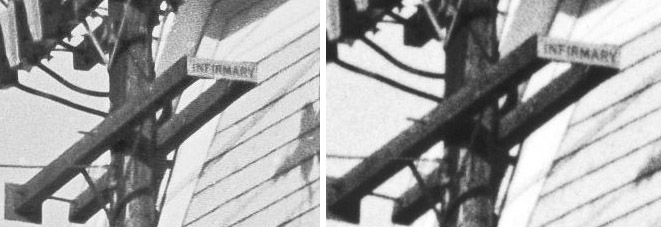

Above left is a portion of a scan of the original Pan-F negative at 5400 pixels-per-inch. At right is a scan of a portion of the 16 by 20 inch print produced from the negative using conventional b&w silver printing paper. It is reproduced here about 6x actual print size. Note that essentially all the detail in the negative is reproduced in the print.

Now it turns out there is another important player in this game, and that is the digital printer. I would argue that digital colour printing today – using ink jet or dye sublimation printers – is at least equal to conventional colour printing in most respects. I am universally happier with my colour prints today that I ever was using the conventional colour darkroom. That has not been my experience with b&w printing. Until I printed one of my earliest D800 b&w images, I had never produced a 16 by 20 in ink jet print – colour or b&w – that required me to use a magnifier to see the finest detail. Now that sounds like I’m saying “we have arrived!” With this result I thought that’s what I would be saying in this article. Not so Fast! One sample does not mark a trend. At this writing, 600 or so D800E exposures later, that one image remains my singular example of such success! For the most part my D800E b&w prints look just like my earlier b&w ink-jet prints: lacking in detail, and especially lacking in texture in the lighter tones.

Here's a Nikon D800E photograph taken with a 50/1.4 AF Nikkor at f/8 and converted to black and white (ISO set to 160, shutter speed 1/800 sec).

At left is pixel-for-pixel crop of the D800E image. At right is a scan of a 16 by 20 in. print of the image made on an Epson 3800 printer at 2880 dots per inch on Epson Hot Press Natural paper. The print is slightly softer than the digital image, but the name of the boat is still quite readable. Nevertheless there is significant loss of fine detail and highlight texture in the print.

I propose to follow up this article with two additional parts, one on the Nikon 24-70/2.8 lens along with the D800E and some related digital issues, and another one concerning the matter of digital printing. In the mean time, above is my one success, taken using an older 50/1.4 AF Nikkor. My successful print was made using the B&W printing mode on my Epson 3800 printer. Obviously I can’t show you the actual full-size print, but from the illustrations above, I think you'll agree that the all-digital result is comparable to the earlier result using the conventional darkroom.

My subsequent experiences with the D800E became very reminiscent of my experiences in the 1980s using rangefinder Leicas with Technical Pan or Pan F film. When one is working near the limits of what is possible, there are a lot of ‘got yas’ that get in the way. Lack of film flatness was one such issue with film, as were curvature of field in lenses, lens alignment, choice of aperture, subject movement, etc. Those frustrations were what drove me to explore the issues and write “The INs and OUTs of Focus” (still available for download here). Some of those frustrations are still with us; some, like film flatness, are gone, but there are a few new ones as well. The Luminous Landscape article “So You Think Medium Format Digital is Easy?” expresses similar frustrations. It comes with the territory when working ‘at the edge’.

Before closing this introduction I’d like to comment on two issues previously raised by others in relation to the D800 and D800E: moiré and auto-focus. Is moiré an issue with the D800E? Yes, I have seen moiré with the D800E, but no more frequently than with other digital cameras – excepting the Leica M9, which has a much bigger issue with moiré. I often don’t see moiré when I expect to, and yet I do sometimes see it when I would not expect to. When I see moiré in D800E images, it is most often in building siding or roof shingles. A puzzling matter is that while using f/11 usually kills the moiré with the M9, it does not seem to do so with the D800E, at least not with the 24-70/2.8. I had expected that even f/8 might kill it with the D800E. At this stage I can only speculate that this might be a lens-related issue: if the out-of-focus image is ‘hard-edged’, I can see the moiré persisting. According to the tests done by Photozone.de the Nikon 24-70/2.8 is a lens that produces a narrow bright outline around the out-of-focus blur circles produced by highlights. In general, I expect most users could opt for the 800E and encounter few moiré problems. And it is usually easy to fix these days in LightRoom 4. Also, in the cotext of black and white photography, it does not always need to be fixed. Sometimes the conversion from colour to b&w will effectively erase the moiré. But one cannot count on it; in at least one case I did not notice the moiré until I had printed the image in black and white. At first I thought it must be an artifact of the printing operation, but more careful study revealed it had been there all along, I just hadn't noticed it. Do I see a left AF focus sensor issue? The answer is clearly no. I have done tests with the 50/1.4 at f/2.8 and see no change in image sharpness or resolution no matter what focus sensor I choose. And yet, I did discover an issue with the 24-70/2.8 lens that could easily get interpreted as an auto-focus sensor issue. More on that in Part II.

Link back to Merklinger's Photo Books